It’s difficult to overstate the contempt Charlotte’s government feels for its citizens.

Though disdain for the people is widely distributed among our elected officials, high-ranking bureaucrats, and well-connected members of the governing class, perhaps no one personifies it like Assistant City Manager Tracy Dodson, whose duties as director of economic development require her to act as the in-house propagandist for powerful interests seeking to monetize our municipal government: Whenever businesses want to pad their pockets with public dollars or stop the adoption of policies that might eat into their bottom lines while benefitting the public, Dodson’s there to do their bidding.

She was the obvious choice to lead the campaign of governance-by-ambush currently threatening the city’s coffers.

On June 3, Dodson unveiled a proposal for the city to spend $650 million in tax revenue to upgrade Bank of America Stadium, home field of the Carolina Panthers and Charlotte FC. She asked Council to take just three weeks to consider what Councilman James “Smuggie” Mitchell described as the “biggest project we have ever funded in the history of Charlotte.” A vote on the proposal is scheduled for June 24.

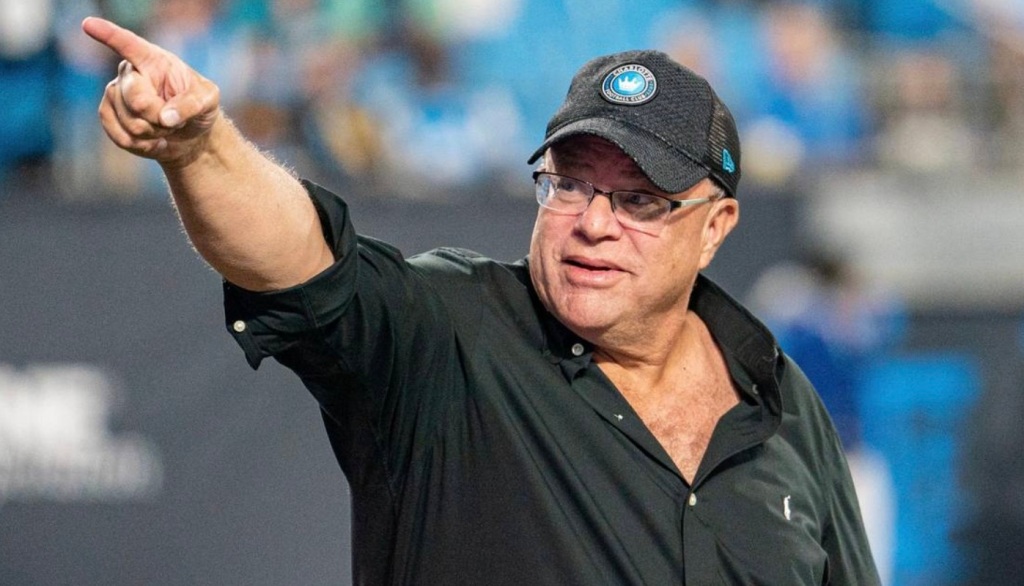

Hedge fund manager David Tepper, who’s worth roughly $20.6 billion, owns both teams and the stadium. Tepper is the 94th wealthiest person in the world.

The concept of a billion dollars is so far removed from the lived experience of virtually everyone on the planet that its real meaning is elusive. If we are to understand Tepper’s wealth, we need to translate it into numbers that ordinary people can appreciate: Suppose a worker cobbled together $10,000 in savings. For him, what would be the equivalent of Tepper forking over $650 million of his own money to cover the cost of the stadium’s renovations? About $315. (Keep in mind that Tepper earned Forbes‘s next-to-lowest philanthropy score because he has given only between 1% and 5% of his immense wealth to charity. So while it sounded generous, for example, when Tepper recently donated $3 million to a Charlotte food pantry, the donation was the equivalent of our worker with ten grand in the bank giving a panhandler less than two bucks. Tepper’s purported good works aren’t evidence of his generosity, but his stinginess. And, of course, there’s something ethically perverse about a billionaire giving a few dollars to a charity that exists only because we live under an economic system that allows people like him to accumulate obscene amounts of wealth while one in five kids in North Carolina wakes up and goes to bed hungry — all while Tepper asks taxpayers to subsidize his privately owned, for-profit business. When we allow such things, I can think only of the Rev. Jeremiah Wright: “God damn America.”)

The stadium’s renovations would include new seats, improved access for people with disabilities, an outdoor pavilion, and upgrades to the stadium’s lighting and HVAC and other mechanical systems.

Funding for the plan would come from city taxes levied against hotel rooms and restaurant sales, which are required by law to be used for tourism-related projects, something the tourism industry jealously guards. When Councilwoman Renee Johnson suggested in early April 2024 that the city consider following Asheville’s lead in asking for legislative permission to spend some tourism money on infrastructure like public transit, the response was swift. Within days, N.C. Restaurant & Lodging Association, a special interest group that advocates for the so-called hospitality industry, criticized the idea. The city quickly fell in line: Mayor Vi Lyles assured the Association that the conversation about the mere possibility of exploring the diversion of some tourism dollars to public infrastructure “does not question or indicate any change in city policy.” Councilman Malcolm Graham went further. He not only described the idea as “terrible,” but said it shouldn’t even be discussed: In a government of, by, and for monied interests, any plan that might infringe on the ability of those interests to financially benefit from public policy must be not only rejected, but expunged from public life. This marks not the preference for one particular policy over another, which is unremarkable, but a rejection of the idea of public discussions about the possibilities of public policy.

The abandonment of liberal ideals — the sort that animate democratic governments that operate in open societies for the benefit of the people — is a logical consequence of crafting government policy to benefit private interests; plutocratic emoluments breed corruption and denigrate the incidents of democracy. When our dominant political narrative casts public officials in the role of vassals to material power and privilege, officials like Graham understandably reject the idea of meaningful public debate and insist on silence lest too many dangerous, genuinely democratic ideas be heard. Indeed, the very existence of government policies like the tourism tax threaten to deprive us of an appreciation of the essential difference between private interests and the public good — a distinction essential to any commonwealth — because such policies are predicated on a trickledown perspective that believes tending to the private interests of the already-wealthy is to serve the public good: What’s good for David Tepper is good for Charlotte. (A nearly half-century of economic experience teaches that, at most, the rest of us get crumbs when government policy tends to the interests of the super-wealthy. The essential premise underscoring our planned giveaway to a billionaire is faulty. Trickledown policies are failures, and the system is rigged: We’ve structured government policy such that billionaires with sports stadiums have dedicated revenue streams while hungry kids and unhoused workers and underpaid teachers do not.)

In exchange for our public dollars, Dodson explained to the city’s economic development committee earlier this month, Tepper’s teams would agree to remain in Charlotte “for up to twenty years.” (Not entirely true: The teams would be obligated to stay for fifteen years. Between years fifteen and twenty, they could buy their way out of the Queen City.)

The promise of a tether comes with an implied threat: Cough up the cash or else. These professional sports teams are not an integral part of the community, but just another asset with which to make money and maximize profit, and if Tepper can’t make here as much as he thinks he can make somewhere else, he’ll happily hit the road. All the gauzy talk of public-private partnerships — an anodyne term that conceals the extortionate nature of corporate welfare like that now under consideration — is mere cover for the predation and sociopathy that lay at the heart of capitalism, at least in its late American form. Tepper sees us not as partners, but prey.

We’re easy targets, our civic insecurity legend. (One small but telling sign of our desperation to prove to others and ourselves that we’re a real place: the voice of Mayor Lyles piped through the terminals of Charlotte Douglas International Airport greeting visitors with the statistic that we’re the fifteen-largest city in the country. Meaningless data informed by arbitrary boundary lines do not give a city soul, class, or substance.)

At its second meeting to discuss the stadium plan, economic development committee members were eager to appease Tepper and competed with each other to fawn over him and his team.

Mayor Pro Tem Dante Anderson embarrassed herself by asking team president Kristi Coleman what WFAE’s Steve Harrison described as “the very definition of a softball question.” She asked, “Do you think that this will help make Charlotte a world-class city?” Coleman replied, “Absolutely.” Harrison went on: “Anderson was pleased. ‘That’s excellent,’ she said.” (Do elected officials really believe “world-class city” means anything? It’s an adman’s drivel, but our leaders seemingly use it as a touchstone for their decision-making. We are lost.)

Councilman Graham ran interference for Tepper by trying to explain away his reputation as an unreliable business partner, a reputation he rightly earned when he abandoned high-profile plans to build the Panthers’ new headquarters in Rock Hill and a soccer practice facility at the site of the former Eastland Mall, while Councilwoman Marjorie Molina asked Coleman, “How do you feel that we can work on the public perception from a Tepper Sports and Entertainment perspective?” — as though it’s our government’s responsibility to help launder the reputation of a failed sports team owner trying to bilk the public treasury to boost his bottom line. It seemingly did not occur to Molina that the public’s perception on this question is right and the governing class’s perception the one in need of correction.

Councilman Ed Driggs was the only committee member to ask any substantive questions. When the renovation plan was unveiled, the Panthers and their enablers in city government sought to give the impression of funding parity: While the city would pitch in $650 million, Tepper would contribute $688 million, including $117 million already spent on recent renovations and $571 million in future expenditures. But, Driggs pointed out, those were mere promises, not contractual obligations. “It would be helpful to have more detail on what’s going to happen and when,” he said. Otherwise, he suggested, it’s just talk. (Driggs nonetheless joined every other member of the committee to endorse the planned giveaway.)

There’s been plenty of time to work out those details in private. When Dodson delivered Tepper’s ransom note a few weeks ago, the plan had been in the works for years: As reported by WSOC, Dodson and others privately briefed Council in January 2023 about the contours of the proposal. Our elected officials and city administrators have known for awhile what was coming. If firm commitments from Tepper weren’t in the plan when it was presented earlier this month, they are unlikely to be in the plan when Council inevitably approves the giveaway next week.

Just two days after the stadium proposal was publicly unveiled, the Queen City’s civic pep squad assembled for a rally to support the proposed billionaire’s bonanza. (Never underestimate the eagerness of the booster class to argue for the right of other well-connected people to use public dollars for their private benefit.) “Now is not the time to go scared to be a big league city,” said Johnny Harris, founder of Quail Hollow Club and former CEO of the real estate firm Lincoln Harris. “We’re twenty years into it; we got twenty years to go. So what do we do? We up-fit the stadium and make it the kind of place we can all be proud of and enjoy and use for that twenty-year period.” Others in attendance who echoed this sentiment included Bank of America Charlotte President Keith Cockrell, Charlotte Center City Partners CEO Michael Smith, and Charlotte Sports Foundation executive director Danny Morrison.

Word might not have reached Johnny over at the club, but with galloping gentrification and expanding inequality, “we” are increasingly unlikely to enjoy and use the stadium. Rather, people like Johnny — and those who think they’re like Johnny — will enjoy and use the stadium while others scrape by on the low-wage service jobs worked by people who tend to Johnny and his friends, the kinds of jobs often created when governments subsidize big businesses: Our plutocrats need an army of poorly paid attendants to cook their meals and landscape their lawns and dry clean their clothes. (An aside: Other than organizing working-class people in a cross-racial alliance, there is perhaps no more imperative project for progressives in the coming decades than to convince middle and upper-middle class workers that they have more in common with the busboys that clear Johnny’s table at the club than they do with Johnny himself. Cultural baubles like football tickets and weekends floating in small boats on Lake Norman tend to convince vice presidents of whatever at this or that bank or business that they are somehow in the same class as Johnny and his peers. They are not. Fundamentally, they are wage-workers, and the sooner they understand that they have more in common with their cleaning ladies and Amazon delivery drivers than they do with the owners and top executives of their employers, the better off we’ll all be.)

It was no accident that Charlotte’s cheerleaders were quickly called into action after the city announced the plan to subsidize Tepper’s teams. Municipal leaders surely expected that calls to use $650 million in public money to pay for improvements to a billionaire’s privately owned stadium would be greeted with popular disapproval, which is exactly what happened.

When the city solicited online comments on the proposal, the results were overwhelmingly negative: Of the 450 comments submitted, according to WFAE, 300 opposed the plan. Only about eighty-five people supported it, and roughly seventy weren’t clearly for or against it. Opponents outnumbered supporters nearly four-to-one.

Dodson was not deterred when she presented the survey results to Council in a way that “dramatically downplayed the negative reaction to the deal,” WFAE reported. “She did not tell council members that most of the respondents are against the deal on principle, that the city should not be subsidizing Tepper.” When Dodson did acknowledge some opposition in her presentation, she couldn’t conceal her condescension. “That’s expected,” she said, suggesting that the essential question raised by the plan — should governments give hundreds of millions of dollars to billionaires? — should be dismissed as too insignificant to seriously consider. Only the little people ask such things.

Dodson’s dismissiveness should not surprise: She made clear when she published Tepper’s demand for tribute that she was not playing the part of a disinterested bureaucrat offering independent expertise and balanced guidance to elected decision makers. Rather, she merely posed as a technocrat while engaging in the work of a partisan seeking to advance the preferred position of her business clients by concealing from the people’s representatives any data, information, or evidence that might cast doubt on the wisdom or propriety of allowing Tepper to raid the fisc.

When Dodson first publicly discussed the proposal, for example, she cited a study commissioned by Tepper that unsurprisingly concluded that the planned giveaway to his private, for-profit business would be good for the Queen City, estimating the local economic impact at $1.1 billion. (The study itself doesn’t appear to have been publicly released, and it’s not posted on the website of its author, Dr. Tom H. Regan of the University of South Carolina. Without access to the study itself, there’s no way to assess the soundness of its definitions, assumptions, and reasoning.) Unmentioned by Dodson was the increasing consensus among impartial experts that public expenditures on sports stadiums do not generate the economic returns promised by the boosters for corporate welfare. As Fred Smith, an economics professor at Davidson College, explained to The Charlotte Observer, the empirical evidence supporting claims of economic benefit like those described in the Tepper-funded study “is incredibly limited.”

Dodson’s failure to provide Council with the full range of expert opinion was dishonest.

Likewise when Dodson tried to spin the nature of the proposed giveaway by arguing that the money “isn’t going to Tepper Sports and Entertainment.” Instead, Dodson said, “This money is going to a community asset, the facility. And the money actually goes to a lot of community businesses.” (Correction: The stadium is not a community asset because the community doesn’t own it. Tepper does. It’s his asset.)

WFAE’s Harrison described Dodson’s characterization as “arguably an oversimplification as well as misleading.” As he explained, “While the city might write a check to contractors, all of the resulting improvements would also be owned by Tepper. … It would be like agreeing to pay for a new roof for your friend’s house. That friend would still own the house and the roof — even if you then claimed the money didn’t go to the friend because you paid the roofer directly.”

So, too, was it less than rigorously honest for Dodson to tell Council that the city wasn’t the only one planning to pitch in. As noted above, to create the appearance of a public-private partnership, Dodson said Tepper would contribute $688 million to the stadium’s upkeep and renovations. But that’s nowhere in the written proposal presented to the city, as Councilman Driggs pointed out. There’s no firm commitment from Tepper, just sales talk from his toadies.

By her willingness to deceive, Dodson made clear that the truth would not detain her, nor does she want it to detain Council: There’s a deal to be inked. What’s a little dishonesty if it earns enough support to get this billionaire’s bonanza done? The mission: By any means necessary, hold on to the votes of just six Council members for a mere three weeks, a timeline that itself shows contempt for the people, who were given no meaningful opportunity to discuss, debate, and decide whether they think one of the world’s wealthiest men should get more than half-a-billion dollars of our city’s money.

Other than the online portal to submit comments — a poor digital substitute for the give-and-take of real deliberative democracy — the only formal opportunity for the people to publicly register their views prior to the day on which Council will vote was a poorly attended two-hour public hearing held in the middle of a work day, another small detail that tells us plenty about our government’s dismissive attitude toward its constituents and their opinions.

Even this minimalist opportunity for public input was not initially planned. The city scheduled it only after a minority of Council members — Dimple Ajmera, Renee Johnson, Victoria Watlington, Tiawana Brown, and LaWana Mayfield — pressed for the public to have at least one chance to weigh in before the day of the planned vote. As WFAE reported, most city officials initially opposed the public hearing because “[i]t could produce several days of negative headlines, if a majority of speakers questioned the deal.”

And that’s the problem Dodson and her colleagues sought to navigate. The deliberations were to be rushed and the opportunities for public input minimized because they knew their plan would be unpopular. The more time they allowed to pass from announcement to vote, the more likely the deal’s opponents could organize and potentially influence at least some elected officials to oppose the giveaway.

The spectre of 2001 haunts Council and its high-ranking bureaucrats: Too much democracy, they know, can threaten the best laid plans of the governing class.

That year, our municipal leaders, at least for awhile, appeared to honor not only the letter, but the spirit, of deliberative democracy. The question: Should the city use $205 million in tax dollars to build a publicly owned uptown arena for the Charlotte Hornets? Council called a referendum that was preceded by a months-long campaign during which supporters and opponents publicly argued, debated, and sought to rally people to their side. The result: Despite pro-arena forces outspending their opponents by a wide margin, voters rejected the plan in a landslide.

Popular disapproval laid bare the gulf between the ideas and priorities of the governing class and those of the people themselves, highlighting for just a moment that our claims to democracy are often more mythical than real. And no wonder: In recent years, as little as 5% of voters decided municipal elections; our city’s government is not a real democracy by any meaningful definition of the word. It is, at best, an elective oligarchy, and in a community with growing inequality and intractable social immobility in which workers can’t find affordable housing while the mayor schemes to illicitly join an exclusive country club so she can hobnob with other members of the city’s elite, there’s little enthusiasm among the rank-and-file for singing the hosannas of a tantrum-throwing billionaire bully and his plan to pad his own pockets with working peoples’ money. The governing class from both major political parties may think it’s savvy to tend to the egos and interests of men like David Tepper, but the people themselves do not.

Charlotte’s experiment with real democracy was short-lived. Following the failed arena vote in 2001, Council was undeterred: Our elected officials voted the next year to build the arena anyway. The governing class’s commitment to meaningful self-rule turned out to be either transient or illusory, but the momentary unmasking of the people’s power risked whetting our appetite for more. Perhaps we would at last really understand that unpopular giveaways — like all unpopular public policies that tend to the interests of the few — aren’t inevitable. Though the people’s policy victory was temporary in 2001, the lesson might always be made more permanent: The people can rule if they will only seize their right to do so.

Our current Council, captive to business interests and convinced the people should learn to accept the oppressive benevolence of their social and political betters, chose, by its endorsement of Tepper and Dodson’s timeline, to learn a different lesson from 2001: Recognizing that eternal vigilance is the price of oligarchy, there would be no feint toward democracy. The people would have neither a meaningful say nor the time to say it.

Nor, in a final act of deceit, were the people to be given the full picture until the last possible moment: We learned from press reports on June 21, just three days before Council’s scheduled vote, that the current plan will require the city to begin negotiating with Tepper regarding a new stadium no later than 2037 — around the time he could threaten to buy his way out of Charlotte. The $650 million Tepper wants now is just a downpayment; we’ve already gotten a first draft of the next ransom note linked to the construction of a likely multi-billion dollar facility. Tomorrow’s blackmail will make today’s look as insignificant as Tepper’s donation to that food pantry.

City leaders deliberately deceived the public in recent weeks by keeping this detail from us, though it seems not everyone was kept in the dark: Remember when Johnny Harris took leave of the club to attend that uptown pep rally at which he said we had twenty years to go with the current stadium? He knew of what he spoke; the well-connected were apparently let in on the secret, but the rest of us could not be trusted with such information. Our elected representatives and high-ranking municipal bureaucrats lied to us because they do not believe the people are entitled to the truth. They believe we deserve only to be managed while suffering the disdain that comes with their dishonesty, a fitting coda to a tale that isn’t really about David Tepper’s material wealth, but about our governing class’s moral poverty.

3 replies on “Beware Democracy”

Thank you for writing this. I live in Malcolm Grahams district. He refuses to engage in discourse with his constituents.

LikeLike

excellent article. Marjorie Molina may on occasion engage in discourse with her constituents, but when she does she is completely unprofessional and acts inappropriate as if we are her children to scold.

LikeLike

Marjorie Molina is more concerned with her “Mayor from Durham” friends, Facebook followers, and TikTok clicks than she is concerned about the district she represents.

LikeLike