Never before have I started this class with a lecture. In the past, we jumped right into the Supreme Court cases we’ll spend the semester reading and discussing. That is how we’ll spend every other evening we’re together, starting next week with Marbury v. Madison, the 1803 decision establishing the power of the judiciary to decide the constitutionality of the actions of other government actors.

But beginning with case law would assume a regularity about our politics and our republic, a regularity that in the present moment seems to me uncertain. I cannot in good faith commence our study of the Constitution and constitutional law without first honestly acknowledging my concerns about the current state and potential fate of the American republic, the very thing on which the relevance of constitutional law depends. These concerns, which I will share with you honestly and in good faith, prompt me to want to talk with you tonight not about the Constitution or constitutional law, but about the relationship between the two and how the latter comes from the former. Exploring this relationship will give us a chance to consider some of the dangers the American republic faces today.

*******

As soon as we undertake to study the Constitution and constitutional law, we confront a challenge.

Consider: The Fourteenth Amendment, which the States ratified in 1868 following the Civil War, prohibits states from, among other things, denying people “the equal protection of the laws.” This is the constitutional provision that our courts currently interpret as barring race-based discrimination.

The text of the Equal Protection Clause reads today exactly as it did when ratified more than 150 years ago, yet the meaning the judiciary has given to this provision has changed over time. In 1896, for example, the Supreme Court decided in Plessy v. Ferguson that the legal regime we would come to know as Jim Crow — that system whereby federal, state, and local governments were permitted to treat Black people differently and worse than white people — did not violate the Equal Protection Clause. But then, in 1954, the Supreme Court decided in Brown v. Board of Education that Jim Crow and its “separate but equal” doctrine did violate the Equal Protection Clause. Over less than sixty years, while the text of the Constitution went unchanged, its meaning changed profoundly.

What are we to make of this change? How do we make sense of it? What is going on here?

We can start to find answers by distinguishing the Constitution from constitutional law. We’re studying constitutional law this semester. By this is mainly meant those decisions handed down by the Supreme Court interpreting the Constitution. Your textbook is full of such decisions, some old, others new, and all of them subject to revision or rejection: what one Supreme Court decides today a different Supreme Court may decide differently tomorrow. Today’s Plessy can become tomorrow’s Brown.

By contrast, the Constitution itself is fixed: The text of its articles, sections, and clauses say today exactly what they said when Congress proposed them and the states ratified them, in some cases nearly 250 years ago. While constitutional law can and does change, sometimes rather rapidly, the Constitution itself does not, at least not without undergoing an onerous amendment process, something done only twenty-seven times since 1787 (and, accounting for the first ten amendments that make up the Bill of Rights, only seventeen times since 1791). While constitutional law is dynamic, the Constitution is static, a piece of parchment kept in a climate-controlled, bulletproof case and watched over by armed guards at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The Constitution and constitutional law are not the same things, even if constitutional law somehow comes from the Constitution.

But how, exactly, does constitutional law come from the Constitution? What does it mean to say constitutional law is a product of the Constitution? How does a centuries-old piece of paper — powerless of itself to do anything but deteriorate — become the living supreme law of the land, that thing which tells us what people and presidents, legislators and judges, cities and states and congresses may or may not, can or cannot, shall or shall not do? How does a piece of paper become a vehicle for real-world power — and, to be clear, that’s our subject this semester: power — that touches on questions of war and peace, taxation and representation, freedom and bondage, equality and caste?

In short, we, the people — our political community and those authorized to wield power in and on behalf of our political community — interpret and give meaning to the Constitution and thereby turn it into constitutional law. This work is undertaken by particular human beings in particular places at particular points in time. That is to say, the people who make constitutional law are socially situated; they are part of a culture and a community, our culture and our community, the American culture and American community — or, perhaps more precisely given the variety of American experiences, they come from parts of the American culture and community.

And here we should consider another meaning of the word “constitution.” When we speak about the Constitution — a proper noun with a capital “C” — we are talking about that old piece of paper kept under lock and key. But when we speak of “constitution” as a common noun with a lower case “c”, we are talking about something else. Merriam-Webster defines this lower-case-c “constitution” as “the structure, composition, physical makeup, or nature of something.” If we say someone’s constitution is weak or strong, timid or brave, flexible or dogmatic, we are talking about the kind of person they are, those characteristics that define them, what they are made of. When we talk in this sense about the American constitution, we are talking about the stuff of which America is made: What do we value? What do we dismiss as unimportant or irrelevant? What do we endorse? What do we reject? What habits, attitudes, perspectives, values, beliefs, and ideas define us? The answers to these questions, which tell us not only who we are but who we want to be, are the things that inform how the Constitution — that old piece of paper — becomes constitutional law. In other words, our national, lower-case-c constitution — that is, what we’re made of — greatly influences, if it does not entirely determine, how the Constitution becomes constitutional law. Put differently yet again, politics — not in a narrow, partisan sense, but in the biggest, broadest meaning of the word that speaks to our foundational, fundamental ideas, values, and beliefs — turns the Constitution into constitutional law: Constitutional law comes from our national, lower-case-c constitution; who we are largely determines what our constitutional law will be.

This is an old idea.

Thomas Jefferson, who wrote our Declaration of Independence, observed in 1785 in his Notes on the State of Virginia, “It is the manners and spirit of a people which preserve a republic in vigour. A degeneracy in these is a canker which soon eats to the heart of its laws and constitution.” Translation: If a community’s lower-case-c constitution degrades such that it comes to reject virtue and embrace vice — or, perhaps more ominously, is no longer able to tell the one from the other — then its laws and the Constitution will reflect the same.

Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville, who toured the United States in the early 1830s and and then wrote his two-volume Democracy in America that sought to explain America and Americans, said much the same thing. Among the subjects Tocqueville discussed were “the main causes tending to maintain a democratic republic in the United States.” He concluded, in part, that what he called “mores” did this work. And by “mores” he meant certain “habits of the heart,” those “different notions possessed by men, the various opinions current among them, and the sum of ideas that shape mental habits.” Tocqueville agreed with Jefferson: a community’s lower-case-c constitution — what it’s made of — will largely determine whether and to what degree it is capable of maintaining a democratic form of government.

So who and what are we? Of what are we made?

Zohran Mamdani, the young state legislator who won this summer’s Democratic Party primary for mayor of New York City, recently gave an answer to the question of who and what we are. On Independence Day, he wrote on social media, “America is beautiful, contradictory, unfinished.” This characterization of America offers a helpful roadmap that we can use to explore ourselves and our country.

Beautiful

There is great beauty in America and the idea of America.

Let’s start with the Declaration of Independence. Listen, really listen, to some of the words you may have heard before: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, —That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” As former President Joe Biden was fond of saying, America is an idea, and the Declaration’s preamble does as good a job as anything of articulating that idea.

I hope you appreciate the Declaration’s radicalism: Those few, simple sentences declared an end to the beliefs that had held men in bondage for centuries. In place of a caste system in which a small number of powerful men ruled over the masses — not just politically, but socially, culturally, and economically — the American colonists declared everyone equal — and self-evidently so! The Founders not only endorsed universal equality, but announced that the purpose of government was to tend to the well-being — the life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness — of the common good, not the narrow interests of a privileged few. They also declared that any legitimate government derives its legitimacy not from God or royal lineage or some hidebound tradition, but from the consent of the governed, which is to say the Declaration endorsed democracy. And, to top it all off, the Declaration claimed not only for its signers and those they represented, but for everyone, a right to rebellion, the prerogative to overthrow any government that rejects equality, democracy, and the common good, any government that places itself in service to the powerful, privileged, or well-positioned.

As historian Gordon Wood observed, “[The American Revolution] was as radical … as any revolution in history.” Hierarchy and caste were out; democracy and equality were in — for all people, in all places, at all times. As the pamphleteer and polemicist Thomas Paine put it in his work Common Sense, which called on the colonies to separate from Great Britain and was published a few months before the Declaration’s adoption, “The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ’Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom … ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now.” The creed that animates the Declaration of Independence is beautiful in its vindication of the rights of all people and its rejection of all manner of shackles that leave the multitudes enslaved to all manner of masters. This was a change of world-historical significance, and adherence to this radical creed is what, in many minds, marks membership in America.

But not all minds. The so-called creedal view of America — that to be an American is to believe in certain ideas, namely those of liberty, equality, and democracy articulated in the Declaration — has always faced challenges. The foundational idea of the Confederate States of America, for example, which rebelled against and sought to secede from the Union, was not universal equality and liberty, but white supremacy in service to race-based chattel slavery. As Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy, said in March 1861, “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea [as that of equality contained in the Declaration of Independence]; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

We needn’t look to the nineteenth century to find powerful voices offering an alternative to the Declaration’s creed. Such voices have spoken up throughout our history.

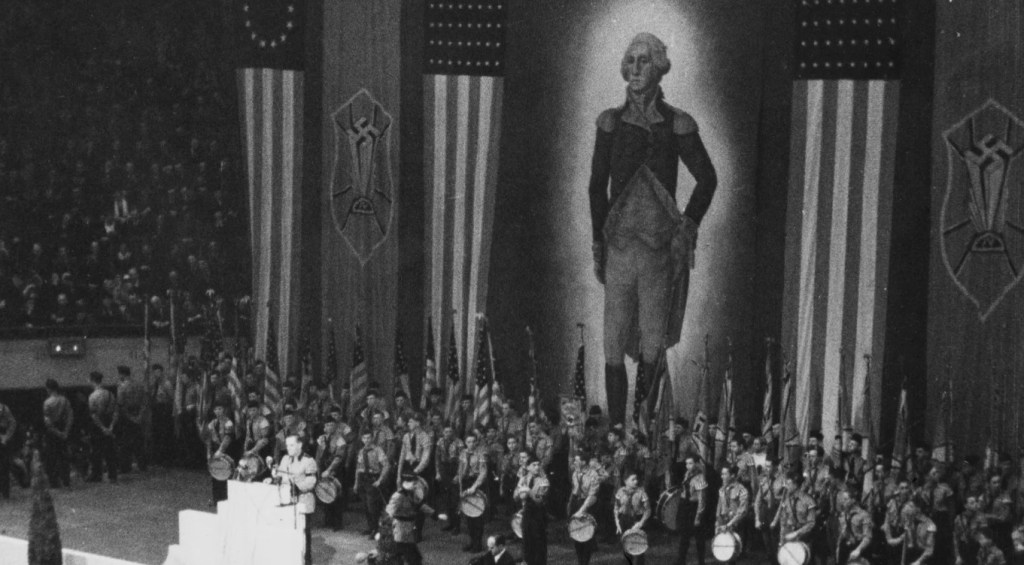

Consider the 20,000 people who in February 1939, just months before the start of World War Two, packed a Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Before a large portrait of George Washington surrounded by swastikas, the German American Bund rallied in the name of an “Americanism” that thought the country needed to be rescued from the grip of racial and religious minorities, delivered from “alien domination” and returned to “True Americans” who were of “white gentile stock.” Like the Confederates, American Nazis didn’t believe in the creed articulated in the Declaration — though, I am happy to report, the roughly 100,000 counter-protesters who showed up to oppose the Nazis surely did. There is beauty indeed when people stand up for the Declaration’s principles and stand up against fascism!

But we also needn’t look to the 1930s for a rejection of the creedal view of America. In a speech this summer to The Claremont Institute, a conservative think tank, Vice President J.D. Vance dismissed the Declaration’s creedal view of America as simultaneously too broad and too cramped: too broad, Vance argued, because America can’t include everyone who agrees with its founding ideals and too cramped because this vision would exclude people who reject the creed but who are undeniably Americans, people that Vance said are today labeled “domestic extremists” by anti-hate organizations because they endorse the truth and legitimacy of racial, religious, or other caste distinctions. We’re left to do some guesswork here because Vance didn’t specify who, exactly, these people are, but we can infer that he meant people like those anti-Semites, racists, and neo-Confederates who marched in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017 while carrying torches and chanting, “Jews will not replace us,” a gathering that President Donald Trump said at the time included some “very fine people.”

Vance suggested that despite these people rejecting the central tenets of the Declaration, they have a claim to be real Americans because the families of some of them have been in this country for generations. As he explained, “I think the people whose ancestors fought in the Civil War have a hell of a lot more claim over America than the people who say they don’t belong.” In other words, a torch-bearing anti-Semite whose ancestors fought for the Confederacy in the name of white supremacy has a superior claim to America than a recent arrival who criticizes that torch-bearing anti-Semite in the name of the Declaration.

Vance’s vision of Americanism requires protecting what he called “sovereignty” from people who are “hell-bent on dissolving borders and differences in national character.” He explained, “You cannot swap ten million people from anywhere else in the world and expect America to remain unchanged” because America is “a distinctive place and a distinctive people.” He then praised the Founders — the same ones who wrote and ratified the universalist message contained in the Declaration — for recognizing the importance of “our shared qualities, our heritage, our values, our manners and customs” and claimed “Americans are not interchangeable cogs in the global economy.” Nor, he added, “in law or commerce should they be treated that way.” All people, it seems, are not created equal, according to the vice president. With these words, Vance rejected the creedal vision of America contained in the Declaration and sought to replace it with something akin to the blood-and-soil nationalism that animated those Nazis who gathered at Madison Square Garden in 1939 and the white supremacists who gathered in Charlottesville in 2017.

In Vance’s words can be heard echoes of the so-called great replacement theory, the idea that white people are being intentionally replaced by people of color and immigrants for the purpose of diminishing the power and social position of white people. Of course, we needn’t infer this administration’s endorsement of the great replacement theory. In July 2025, while vacationing in Scotland, President Donald Trump told reporters that immigration into Europe constituted an “invasion.” “On immigration,” he said, “you better get your act together or you’re not going to have Europe anymore.” These remarks defy any reasonable interpretation except that immigrants of color pose a threat to the very idea and existence of Europe, which stands in for all of the so-called western world, including the United States.

In neither Vance nor Trump’s words is there any suggestion that they endorse the idea of America found in the Declaration. To them, “all men are created equal” doesn’t mean all men are created equal. Gone is the idea articulated by Emma Lazarus and posted inside the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty that “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” may all and equally claim the promise of America without exception or qualification. According to Trump and Vance’s vision of America, not everyone is welcome; not everyone is qualified; not everyone counts; not everyone, to use the language of the Declaration, is self-evidently a part of the free family of man. The radical egalitarianism of the American Revolution is reduced to a system that reproduces and reenforces social and political castes in the name of heritage and tradition, which, given our history, are unavoidably and significantly influenced by race and ethnicity.

But back to the Founders and the beauty of their project. They declared their independence by invoking freedom, equality, and the right to self-government as the essence of a universal human condition. That’s all fine and well as a matter of political philosophy, but then came the hard work of turning political theory and democratic rhetoric into the architecture of government. The Articles of Confederation, America’s first experiment in national government, was a flop. They created a loose confederacy of states with no meaningful national government; the confederation was little more than a league of friendship that threatened to transform the colonies that had united to overthrow King George into petty rivals separated by their own narrowly defined self-interest. After a few turbulent years came the Constitution, drafted by fifty-five men who met in secret in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. The states ratified their handiwork in 1788.

Ratification was not a given; indeed, many colonists opposed the Constitution because they feared it would create a too-strong national government that could become a vehicle of tyranny just as they had thrown off the king. The Constitution required at least nine of thirteen states to ratify it before it would become effective. Ratifying conventions in some states, including New York, were hotly divided. It was in New York that the so-called Federalist Papers were published as part of the ratification debate. Written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, but published anonymously under the pseudonym Publius, the Federalist Papers is a series of eighty-five essays that argued in favor of the Constitution’s ratification. Reading the Federalist Papers today can tell us a great deal about the government established by the Constitution, but the authors’ work also tells us a great deal about the importance of our lower-case-c constitution, the stuff of which we are made, in making any system of democracy work.

Throughout the essays, Publius regularly calls upon or assumes the importance of virtue. In Federalist No. 55, which discusses the composition of the House of Representatives, the author wrote, “As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form.” In other words, democracy assumes its citizens possess and will pursue virtue more faithfully and steadfastly than those who live under other systems of government. To believe otherwise, Publius wrote, would be to believe “that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain [people] from destroying and devouring one another.” Self-government depends on faith in, and fidelity to, personal and civic virtue. Federalist No. 57, which also discussed the House, observed, “The aim of every political constitution is, or ought to be, first to obtain for rulers men who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society; and in the next place, to take the most effectual precautions for keeping them virtuous whilst they continue to hold their public trust.” Again, virtue was central to the Founders’ understanding of good government. In fact, good government was impossible without it. And in Federalist No. 51, which addressed the system of checks and balances built into the Constitution, Publius wrote, “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” Achieving fairness and giving each their due — among the highest virtues — was the very purpose of the government to be created by the Constitution.

So while Hamilton, Madison, and Jay spent much of their effort crafting arguments about the structures and mechanisms of government, behind those structures and mechanisms, the authors assume and suggest, must be a necessary commitment to the things Tocqueville described as habits of the heart: No matter what governmental structures are put in place, if the people choosing their representatives and manning the levers of power are not good people — if they reject virtues like honesty, decency, and honor while embracing dishonesty, indecency, and dishonor — no self-government will be long capable of discharging its duty to promote and safeguard the well-being of everyday, ordinary people without regard to caste, status, or position. Indeed, a self-government whose people and representatives exalt dishonesty, indecency, and dishonor will not long last, but will collapse into some form of tyranny.

As we know, Publius’s argument prevailed: New York’s ratifying convention narrowly approved the Constitution, as every state’s eventually did. Thus began our current experiment in self-government.

Among the most insightful observers of this experiment was Abraham Lincoln, the man who would lead the Union to victory in the Civil War. In January 1838, long before he was elected President in 1860, Lincoln, then twenty-nine years old and a member of the Illinois state legislature, gave an address to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois in which he, like Tocqueville and the Founders, emphasized the relationship between the perpetuation of America’s free political institutions and good character — or, to use our language, a community’s lower-case-c constitution. He praised the Founders in the language of virtue: they were hardy, brave, and noble, he said. The American republic was the fruit of their endeavors and, importantly, their character: Good men created good government. Now, Lincoln said, his generation had a duty to preserve the project of human liberty and equality bequeathed by the Founders, to promote and protect what an older Lincoln at Gettysburg would describe as “a new birth of freedom” and “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” We needn’t worry, Lincoln argued in 1838, that the American project will be felled by outside forces or foreign invaders: “All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth … in their military chest; with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.” No, Lincoln said, if America’s project of self-government is to die, we shall be the ones to kill it: “At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected?” he asked. “I answer, if it ever reaches us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

Lincoln then described how such destruction may arise from within, highlighting the actions of lynch mobs: white men acting outside the law who, motivated by real or apparent grievances, targeted people, often African-American men and boys, for public, lawless assaults and executions. Lincoln described one “horror-striking” scene in St. Louis, Missouri in which “[a mixed-race] man, by the name of McIntosh, was seized in the street, dragged to suburbs of the city, chained to a tree, and actually burned to death; and all within a single hour from the time he had been a freeman, attending to his own business, and at peace with the world.” Viciousness — the abandonment of those civic virtues necessary for effective self-government — lay at the root of mob law, according to Lincoln: “[W]henever the vicious portion of population shall be permitted to gather in bands of hundreds and thousands, and burn churches, ravage and rob provision stores, throw printing presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure and with impunity; depend on it; this Government cannot last.” (Lincoln’s remarks about destroying printing presses and shooting editors are likely a reference to Elijah Lovejoy, a white man, Presbyterian minister, and abolitionist newspaper editor whose printing presses were destroyed by pro-slavery mobs on multiple occasions and who was murdered by such a mob the year before Lincoln’s address.) The way to avoid losing America, Lincoln argued, was, in part, to cultivate “general intelligence” and “sound morality” among the people. A people without virtue — self-control, kindness, and fellow feeling, honesty, decency, and honor — would lose the republic. Our lower-case-c constitution is vitally important to our system of self-government, Lincoln explained.

Lincoln’s warnings about the risk of national suicide came to pass with the Civil War, which was fought over the questions of whether and to what degree one race of people should be empowered to enslave another race of people. The Civil War, which is the closest we have so far come to committing the national suicide Lincoln contemplated, tested whether we, as a nation, really believed in our founding creed of human equality and liberty. Lincoln did his part: He successfully lead the Union through the conflict, issued the Emancipation Proclamation that freed all slaves held in territory then in rebellion, pushed for the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, and signed into law the bill creating the Freedman’s Bureau, which sought to provide food, housing, medical care, education, and other assistance to newly freed slaves. He paid for this work with his life.

After four years of bloody conflict, that side of the fight that sought to preserve the Union and eventually committed itself to abolishing slavery prevailed. The Confederacy was defeated, and the Constitution was amended to abolish slavery, grant birth-right citizenship to everyone born in the United States, guarantee due process of law and the equal protection of the laws, and protect the right to vote from racial discrimination. It is from these amendments — and, importantly, the ethical commitments that animate them — that America, over the last 150 years, has made significant progress in promoting, protecting, and defending personal liberty and equality. In important ways, the anti-caste radicalism of the American revolution has been vindicated. Our commitment to equality and liberty — our lower-case-c constitution, that stuff of which we are made — influenced the subsequent development and interpretation of the Constitution in the direction of a greater realization under the law of the equality and liberty proclaimed by the Founders. This is the beauty of America.

Contradictory

But only imperfect and incomplete beauty, which brings us to the second way Mandami characterized America: contradictory.

Thomas Jefferson, who penned the Declaration’s ode to liberty, equality, and democracy, owned hundreds of slaves over his lifetime, at least one of whom, Sally Hemmings, he sexually assaulted. Likewise did George Washington and James Madison own slaves. Indeed, of our first twelve presidents, only two — John Adams and his son, John Quincy Adams, both of Massachusetts — did not own slaves at some point in their lives. Many of our Founders just didn’t see the contradiction between their rhetorical commitment to liberty and equality and their actual participation in human bondage, a practice shot though with cruelty and degradation.

The Constitution made room for slavery, though the word “slavery” never appears; the Founders used euphemism or ambiguity to describe slavery. The Slave Trade Clause, which prohibited Congress from banning the importation of slaves until 1808, read, “The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight.” The Fugitive Slave Clause, which compelled free states to participate in the capture and return of runaway slaves, read, “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.” The Three-Fifths Clause, which allowed slave states to count three-fifths of their slaves for purposes of apportioning representatives in Congress, read, “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.”

A republic founded on the ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy, at the moment of its very creation, made plenty of room for human bondage, racial caste, and slavocracy. As Mandami said, contradictory.

And not just at the Founding. Through the first half of the nineteenth century, Congress sought to accommodate the slave power through the Missouri Compromise in 1820 and the Compromise of 1850, the former balancing the admission of Maine into the Union as a free state with the admission of Missouri as a slave state and allowing for the expansion of slavery in western territory located below a certain latitude and the latter abolishing the slave trade in Washington, D.C. and admitting California as a free state while allowing New Mexico and Utah to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery and strengthening the power of slave owners to recapture runaway slaves. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed those territories to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise’s limitation on slavery in certain territories. Then, in 1858, the Supreme Court handed down the infamous Dred Scott decision in which Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote on behalf of the Court that Congress lacked all power to prevent the expansion of slavery into new territories and that Black people possessed “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Civil War, initiated by slave-holding states in the wake of Lincoln’s election to the presidency on a platform committed to stopping the expansion of slavery, followed three years later. The Confederacy lost, and the nation ratified the Civil War Amendments, which were intended to dismantle slavery and its legacy.

But all was not as it seemed: Despite the Civil War Amendments that were meant to protect newly freed slaves, America’s race-based caste system would persist for at least another hundred years. In the decades following the Civil War and Reconstruction, America inflicted on Black people legal discrimination that looked very much like slavery, what Pulitzer Prize-winning author Douglas A. Blackmon calls “slavery by another name,” a combination of debt peonage and convict leasing that swept up Black men for phony, yet legally recognized, crimes — often vagrancy, the “crime” of being unable to prove one was gainfully employed. Such convicts were then farmed out to businessmen and industrialists for the duration of their sentences, expected to labor in dangerous, disease-infested conditions. Many died from illness or accidents.

Those who avoided this fate often found themselves in sharecropping arrangements whereby landowners allowed them to farm a certain portion of land in exchange for fees to be paid for rent and supplies, with the fees to be paid from the crop to be harvested. The harvested crop was often deemed insufficient to cover the fees, which would result in the sharecroppers continuing to be bound to the contract, effectively enslaved. If the sharecroppers sought to simply walkaway, doing so could be treated as a criminal act, which could result in arrest, conviction, and sentencing — leading right back to the very place they had sought to escape, or perhaps into the maw of convict leasing. The law not only accommodated these arrangements, but generated them.

Our national, lower-case-c constitution continued to believe after slavery’s formal abolition that a racial caste system was acceptable, and the Constitution was interpreted accordingly, most famously in Plessy v. Ferguson, which declared in 1896 that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits states from denying people “the equal protection of the laws,” did not prohibit states from relegating non-white people to separate, inferior train cars. Even Justice John Marshall Harlan, the lone dissenter in Plessy, endorsed the view that the white race was superior to non-white races and explained that while he would have invalidated the Louisiana law mandating separate trains cars for white and non-white passengers, laws against integrated schools and interracial marriage were surely consistent with the Equal Protection Clause. “Our constitution is color-blind,” Justice Harlan famously wrote, even as he endorsed white supremacy as a biological fact and social and cultural imperative.

Notwithstanding Harlan’s dissent, the Court enshrined the doctrine of “separate but equal” into the Constitution, and it would remain there through the middle of the twentieth century. An entire legal regime of separate, inferior treatment followed Plessy. The Constitution — the exact provisions in force today — made room for racial discrimination because we, as a nation, decided it should. Racism was part of the stuff of which we were made, and our institutions, including the law, followed suit. Access to housing, education, healthcare, jobs, restaurants, shops, transportation, movie theaters, public pools and beaches, libraries, restrooms and water fountains, voting booths, juries, public office, and more were regulated on the basis of race.

So, too, was the protection of physical bodies, especially the physical bodies of Black men and boys. Extra-legal racial violence — to be clear, violence perpetrated by white people mostly against Black men — plagued parts of the nation. The lynch mobs Lincoln described in the 1830s returned with a vengeance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Equal Justice Initiative, which opened The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in 2018 to bear witness to the history of racial terrorism inflicted on African-Americans from the 1870s to the 1950s, estimates more than 4,000 people were murdered in racist lynchings. And know this: While Black men were sometimes kidnapped and killed in the dead of night by masked men, lynchings were sometimes community events: advertised in advance in local newspapers, conducted in broad daylight, attended by upstanding, respectable white people, including law enforcement officers and elected officials, and memorialized in so-called lynching postcards, which were exactly what they sound like: postcards that included photographs of the mutilated, battered, or burned corpses of the Black men who were tortured and murdered in public spectacles by merchants, businessmen, and other reputable members of the community. Often the postcards featured the smiling, beaming faces of the perpetrators of, and witnesses to, this brutality, white people proud of the terror and suffering they had helped to inflict in the name of white supremacy. Christine Turner, who produced a short 2021 documentary called Lynching Postcards: Token of a Great Day, describes a postcard created to memorialize the 1915 lynching of Will Stanley in Temple, Texas. Stanley, who was accused of assaulting a white woman, was burned alive before a crowd of thousands of people. The photograph on the front of the postcard depicts the charred remains of Will Stanley surrounded by dozens of the white people who murdered him. On the back of the copy of the postcard that Turner found was written the sender’s message, “This is the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe.” While the Constitution’s text said Black men couldn’t be denied liberty or equality, our lower-case-c constitution approved of racial violence and discrimination and thereby gave that meaning to the Constitution and American life.

That America long endorsed racism despite the Constitution’s guarantee of equality isn’t, as the current regime would surely say, “woke,” but obvious, a reality that can be denied only by a willful refusal to acknowledge our history. Consider the title of legal scholar Michael J. Klarman’s book: From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. The Civil War Amendments, which would be the vehicles for dragging the country from Jim Crow to Civil Rights, were ratified in the late 186os and early 1870s. Those amendments read today exactly the way they did in the mid-nineteenth century. The Constitution hasn’t changed, but America’s lower-case-c constitution has. To use Klarman’s phrasing, we went from Jim Crow to civil rights not because the Constitution was different when the Court decided Brown in 1954 than it was when the Court decided Plessy in 1896, but because our lower-case-c constitution underwent a change: Within our political community, enough of us for long enough decided that treating people of color as second-class citizens — or as no people or citizens at all — was unacceptable, so we read such mistreatment out of the nation’s charter, which had been interpreted otherwise for decades. We count this as progress, as we should, but it is, at best, a work in progress, and certainly one rife with contradiction, as Mandami said.

Unfinished

We are left, then, with Mandami’s final characterization of America: unfinished.

We are very much a work in progress. America is ours to make of it what we will. What shall it be for us? Democracy or authoritarianism? An open society or a closed one? Freedom or tyranny? Large-souled or small? Kind or cruel? Honorable or dishonorable? Decent or indecent? Honest or dishonest? Will we pursue the legacy of American beauty bequeathed to us by the Founders, which promises us liberty, equality, democracy, and the achievement of the common good among our friends and fellow countrymen? Or shall we instead pursue the dark contradictions, the worst of the American tradition and legacy, that they also handed down to us? These are real questions. Their answers are to be determined, and they are to be determined by us.

Here we must unavoidably and forthrightly consider the current political moment in which we find ourselves. There is no other way to ponder these questions but in light of our current circumstances and our recent choices. Now, to be sure, we needn’t and shouldn’t engage in a narrow partisan examination of America in 2025, but we also needn’t and shouldn’t turn a willfully blind eye to the behavior that we, as a political community, are currently experiencing and endorsing. If we have access to the truth — and, with our eyes and ears and good sense, we surely do, even if imperfectly so — we should bear witness to it, name it, and tell it to the best of our ability, and while we should also always strive to remember our own fallibility, we should’t use our fallibility as an excuse for inaction, acquiescence, or silence.

As is often the case when contemplating the ways that power seeks to distort, silence, or deny the existence of the truth, as is often the case when we wrestle with questions of democracy and authoritarianism, George Orwell offers us some helpful guidance. In a January 1939 book review, as Hitler’s regime threatened Europe, Orwell wrote of a volume recently published by British philosopher Bertrand Russell, “If there are certain passages of [the book] which seem rather empty, that is merely to say that we have now sunk to a depth at which restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men.” Powerful political and cultural forces sometimes tempt us to deny obvious truths: power invites us to adopt its lies as our own, and we accept. Orwell encourages us to reject such invitations. Immediately after World War Two, Orwell wrote in his essay Politics and the English Language that “political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible,” which is just another way of saying power seeks to conceal the truth of its actions. Referring to the atrocities committed by the Stalinist regime in the Soviet Union, Orwell offered an example of how power uses language to lie: “People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: This is called elimination of unreliable elements.” Power seeks to hide its ugliness from those who might object were its ugliness honestly acknowledged and described, and too many people too often go along with the deception.

So it is today in America. Plain, ugly truths about who and what we are doing and becoming abound, but there exists a temptation to deny, rationalize, or otherwise conceal these ugly truths, perhaps especially from ourselves. We should resist this temptation and instead try to speak obvious truths plainly.

Telling the truth as best we can is consistent with our work here at an American university, and at this university in particular.

Generally speaking, one function of higher education is to seek the truth, which we should admit is often uncertain, messy, or complicated. We can account for these limitations while still committing ourselves to seek and tell the truth to the best of our ability. Once again, our admitted inability to achieve perfect knowledge or understanding can’t justify nihilism, know-nothingism, or a willful refusal to see what’s before us.

More specifically, Queens is a place committed to the truth. Each of you, upon your matriculation, signed the Queens Honor Code, which commands you to behave honorably and honestly in your lives. Queens describes its honor code as a “keystone” in the university’s life and the lives of its students. The Honor Code requires you to behave respectfully and responsibly. It imposes standards of personal accountability on you at all times and in all things. To violate the Honor Code is to discredit yourself. The pledge itself states, “I will endeavor to create a spirit of integrity.” When you sign the Honor Code, you pledge yourself to “truthfulness and absolute honesty,” and you promise “to treat others with respect.” Honesty, decency, honor, and integrity: these are the obligations you have taken upon yourselves, and they are among the values Queens has said are the essence of the university’s life. And just as Queens and its students expect these things of each other, surely we can apply these standards to those in positions of political power. If our nation’s leaders are themselves running afoul of these important duties, then surely we here at Queens should speak up.

And so I shall try.

My thesis is that we live in a time and place where the beautiful promise of the American project risks being overtaken by the ugliness of America’s dark contradictions, that liberty, equality, and democracy, honesty, decency, and honor, kindness, compassion, and fellow-feeling are at risk of being degraded and discarded by the current American regime and its supporters and enablers.

Let’s start with issues of race and immigration, a fitting place to begin in a nation whose history includes centuries of race-based chattel slavery, the forced removal and ethnic cleansing of indigenous peoples, immigration laws that sought to exclude or limit the entry of people of color, concentration camps for people of Japanese ancestry during World War Two, and the racist caste system we call Jim Crow and from which we are still recovering.

Prior to his first run for President, Donald Trump was among the leading voices of the so-called birther movement, which pushed the baseless theory that then-President Barack Obama was born in Africa and therefore ineligible to be President, an argument inextricably bound up with Obama’s race. Trump continues to this day to refer to Obama by his full name — Barack Hussein Obama — in an obviously racist attempt to invoke a vague sense of danger because of Obama’s foreign-sounding middle name, one that Trump hopes will cause people to think of Islamic terrorists from the Middle East when they think of the forty-fourth president. This rhetorical tick is consistent with Trump’s previous statements that Obama is secretly a Muslim and, therefore, somehow not a real American. This argument casts all Muslims, Arabs, and people with brown skin as somehow less American than the so-called real Americans Trump claims to represent.

When Trump launched his presidential campaign in 2015, he described Mexicans seeking to enter the country as murderers and rapists, a bold claim from a man who has since been convicted of multiple felonies, indicted for still others, bragged on tape about grabbing women “by the pussy,”and was recently found civilly liable for sexual abuse in the rape of author E. Jean Carroll. Trump has also said immigrants are “not human” and are “poisoning the blood” of the country and has suggested they are snakes or vermin, all of which dehumanizes people of color, some of whom come from what Trump once described as “shithole” countries. He also said on the 2016 campaign trail that he wanted to ban all Muslims from entering the country, attempted to impose such a ban in his first term, and recently imposed another ban that prevents people from coming to the United States from twelve countries — all of them overwhelmingly populated by people of color. This most recent travel ban coincides with the dismantling of USAID, the United States Agency for International Development, which provided humanitarian assistance to poor countries around the world, many of them populated by people of color. Experts have predicted that the decision to dismantle USAID will result in the deaths of roughly 14 million people over the next five years, one-third of them children. The deaths projected to be caused by this policy decision are the equivalent of nearly two-and-a-half Holocausts. These policy changes also coincide with the Trump administration’s recent decision to expedite the arrival of 59 white Afrikaners from South Africa, who were welcomed at the airport by a high-ranking member of the State Department. The administration wrongly claims the Afrikaners were being mistreated by the South African government, which is overwhelmingly Black and continues to pursue policies intended to dismantle the legacy of decades of Apartheid. And, of course, there was plenty of dishonest, racist rhetoric on the campaign trail last year, perhaps most infamously when Trump claimed that Venezuelan gangs had overtaken the city of Aurora, Colorado — a claim disputed by the city’s Republican mayor and chief of police — and that Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio were eating the dogs and cats of their neighbors.

Once he reentered office this year, Trump sought by executive order to end birthright citizenship, a guarantee written into the Fourteenth Amendment. The clause is simple and straightforward: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Courts have long recognized the plain meaning of this constitutional text: If you are born here, you’re an American citizen, but Trump wants the judiciary to change its mind to aid his campaign against immigrants. Trump’s administration has also stripped Temporary Protective Status, which allows people from fragile or dangerous nations to seek refuge here, from Haitians, Venezuelans, Cubans, and Nicaraguans — with the stroke of a pen, rendering these people undocumented and subjecting them to deportation, sometimes after decades in the United States during which time they built lives, families, careers, and community ties.

The work of rounding up people for deportation falls to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, which is quickly becoming an American secret police: masked, unidentified men and women in street clothes and unmarked cars hunting down fellow human beings, inspiring terror, and snatching people off the street — often violently, without an arrest warrant of any sort, and on the basis of racial profiling, whisking them away from workplaces, schools, parking lots, automobiles, courthouses, hospitals, and other public places and carrying them far from their lives, families, and homes. Some of those rounded up are rotting in detention centers sprinkled across the United States. Others were sent to the so-called Alligator Alcatraz, a hastily built camp in Florida whose supporters revel in and celebrate its crowded, inhumane conditions in which dozens of people are held together in cages under tents in the middle of a swamp. Some politicians, in a competition to see who can be seen as most gleefully inflicting gratuitous suffering on the most vulnerable among us, have expressed a desire to build similarly inhumane facilities in their states. Others want to see their fellow human beings sent to the U.S. military base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, which they hope will function as a sort of legal black hole to which people can be sent on the say-so of the government without any recourse to challenge their detention. And still other detainees were sent to the CECOT prison in El Salvador, a facility intended to hold people without charge, trial, or conviction until they die. Let’s speak this last point plainly: The current American regime struck a deal with a proudly self-styled dictator to ship hundreds of human beings to a modern-day concentration camp where they could be tortured and held indefinitely without any due process and without ever being convicted of a crime. When video footage of people’s treatment in this Salvadoran dungeon was shown at a recent political rally thrown by President Trump, the scenes of abuse and degradation that we inflicted on our fellow human beings were greeted with cheers and chants of “USA! USA! USA!” Our countrymen met cruelty and suffering with celebratory glee. The beauty of America’s promise shivers and shakes under an assault by our darkest, meanest contradictions.

Despite the attempts of the current American regime to dehumanize our fellow human beings — and let’s be clear: describing people as illegals or snakes or vermin or invaders is meant to do just that so the public will better accept their abuse — those victimized in this cruel dragnet are not bogeymen or monsters. Nor are they statistics or abstractions. They are individual, flesh-and-blood human beings with names and lives and stories, each of them among the “all” that our Declaration says were created equal and each of them among those who possess God-given dignity, worth, and rights. Let’s take a few minutes to meet some of them.

There’s Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran refuge who came to the United States in 2011 as a teenager to escape gang violence in his home country. A judge ordered that he could not be removed to El Salvador because of his well-founded fear of gang persecution. In March 2025, he was among the 238 men sent to CECOT in El Salvador, which violated the previously entered judicial order barring his deportation to that country. He was sent there on suspicion of being a gang member, an allegation he was given no opportunity to challenge. An attorney for the Justice Department acknowledged in court that sending Abrego Garcia to El Salvador was an error. For his candor toward the tribunal, which the rules governing lawyers required, this attorney was fired. The administration then undertook a campaign to lawlessly resist court orders to facilitate Abrego Garcia’s return to the United States, finally relenting and bringing him back to the country only to charge him with crimes related to human smuggling — crimes the Justice Department started investigating only after Abrego Garcia’s mistreatment became a symbol of the government’s lawlessness. Abrego Garcia, who has lived in Maryland for ten years and is married to an American woman with whom he has an American-born son, has described the criminal charges as “preposterous.” Now, as Abrego Garcia awaits trial on these charges, he has been informed that if he pleads guilty, the government will deport him to Costa Rico; if he insists on his rights to the presumption of innocence and a jury trial, the government has said it will deport him to Uganda, an African nation to which he has no ties whatsoever and that is so dangerous that the United States government warns Americans not to travel there. This is not governance, but extortion. For now, Abrego Garcia has told the government he has no intention of pleading guilty to crimes he didn’t commit, and so the regime is now trying to send him to Uganda, a move at least temporarily blocked by a federal judge. If he is banished there, Abrego Garcia will be separated from his wife, his son, and the life he has built here.

There’s Andry Hernandez Romero, a gay makeup artist from Venezuela who came to the United States in 2024 to seek asylum because of his sexual orientation and political beliefs. He was also among the 238 men sent by us to CECOT because he was a gang member, a false allegation based solely on a government agent’s faulty interpretation of a couple of his tattoos, and one he was denied an opportunity to contest before being shipped to the camp. Andry was recently released and returned to Venezuela, and the media is reporting he was beaten, tortured, and sexually assaulted while held at the camp.

There’s Mahmoud Khalil, a legal permanent resident and Columbia University graduate student who participated in pro-Palestinian protests in 2024 and was seized by ICE in 2025 because Secretary of State Marco Rubio believes the United States is so fragile and delicate that Khalil’s activism harmed U.S. foreign policy. Let’s say that again: Khalil was detained for months because a high government official said his political activity, which should be protected by the First Amendment, rendered him eligible for removal from the nation where he and his American-born wife are building a life that includes a now-newborn baby whose birth Khalil missed because the government refused to release him to allow to him to attend. Instead, he listened over the phone as his wife gave birth. A federal judge recently ordered Khalil released because his detention was illegal.

There’s Mohsen Mahdawi, another Columbia University student and pro-Palestinian activist who was arrested by ICE at his citizenship interview, again because Secretary of State Rubio declared his political activism — core political speech that is supposed to be protected by the First Amendment — harmed U.S. foreign policy. Mahdawi, who was recently ordered released from custody by a federal judge, is a permanent resident alien and has lived in the United States since 2014.

There’s Rumeysa Ozturk, a doctoral student at Tufts University who was lawfully in the United States on a student visa when she penned an op-ed for her school newspaper in March 2o24 criticizing the political state of Israel and decrying the killing of Palestinians in Gaza. Once again, this is core political speech that a free, open society seeks to protect. Secretary of State Rubio declared Ozturk’s presence in the country dangerous because of her authorship of the column in her student newspaper: he revoked her student visa without her knowledge, and she was then arrested outside her home by a group of masked, unidentified federal agents as she went to break her Ramadan fast with friends. A bystander who filmed the incident believed it was a kidnapping because it looked like one. In May 2025, a federal judge ordered Ozturk released because there was no evidence to support her continued detention.

There’s Narciso Barranco, an undocumented 48-year-old father of three United States Marines who was violently detained by federal agents while working his landscaping job in June 2025. When he ran from them, a half-dozen masked agents held him down while one of them repeatedly punched him. Barranco is from Mexico and has lived in the United States since the 1990s. He has no criminal record.

There’s Paola Clouatre, the twenty-five-year-old wife of a United States Marine veteran who entered the country from Mexico with her mother more than a decade ago to seek asylum. Clouatre applied for permanent resident alien status after the couple married in 2024. She had been ordered deported years earlier when her mother failed to appear at an immigrations hearing. As she and her husband attended an appointment to seek to remedy her status, she was detained. She and her husband have two American-born kids, a two-year-old son and a three-month-old infant who was still breastfeeding when Clouatre was detained and separated from her family. She was recently released when an immigration judge suspended her deportation order.

There’s Heydi Sanchez Tejeda, a Cuban immigrant and wife of an American citizen who was detained and deported in April 2025. Sanchez Tejeda entered the country five years ago to seek asylum and was here under a so-called temporary stay permit that does not grant legal status. Her application for a green card was pending when she attended an immigration appointment to check in with ICE. She is the mother of a one-year-old child that she was breastfeeding and who is an American citizen like the child’s father. The government has made no meaningful argument that forcibly separating a mother from her one-year-old, breast-feeding child is in the mother’s best interests, the child’s best interests, or the nation’s best interests. Sanchez Tejeda remains in Cuba, separated from her husband and infant child, who will be indefinitely deprived of its mother’s physical love and presence.

There’s Luis Alvarez, a construction worker and Good Samaritan who in June 2025 ran into the ocean to help a nine-year-old girl who was being attacked by a shark, placing himself in great danger to help rescue her. He was recently pulled over for driving with his headlights off and was charged with driving without a license, a misdemeanor for which he was previously charged on three occasions. Alvarez, who was authorized to work in the United States, is from Nicaragua and is now facing deportation because our government believes it is in the public interest to remove this Good Samaritan from amongst us.

There’s Donna Kashanian, a 64-year-old Iranian mother, wife, PTA member, and community volunteer who was seized in the garden of her New Orleans home by ICE agents and whisked away without her family being notified. The family found out what happened to Kashanian because a neighbor happened to see her capture. Kashanian has been in the United States since 1978, when she arrived on a student visa. She later applied for asylum due to her father’s connections to the Shah, the Iranian dictator and American ally who was overthrown in 1979 by the Islamic Revolution. Though her asylum application was denied, her removal had long been stayed so long as she complied with immigration requirements, such as regular meetings with immigration officials. Kashanian is married to an America citizen and they have a now-grown American daughter. She is surely the kind of person that makes America better, maybe even makes it great, but Tricia McLaughlin, a spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security, was unmoved after Kashanian’s seizure, saying simply, “[Donna] Kashanian is in this country illegally. She exhausted all her legal options.” In July, Kashanian was released, and her efforts to secure legal immigration status will now continue.

There’s Mahdi Khanbabazadeh, an Oregon chiropractor and Iranian native seized by ICE agents as he brought his young American-born child to school. He pleaded with the masked agents to be allowed to drop off his child before they seized him, telling them, “There is a baby in the car. Is it hard to wait three minutes?” In today’s dark America, the answer is “yes”: ICE agents interpreted this request as resisting arrest, smashed through the car window, and seized him in front of his child. Khanbabazadeh, who first came to the country on a student visa, is married to an American citizen and had recently completed an interview for a green card.

There’s Ayman Soliman, an Egyptian man and imam at an Ohio mosque. He arrived in the United States in 2014 when he fled Egypt because of his work as an independent journalist who advocated for democracy in his home country. The United States revoked his asylum status in June, and ICE agents seized him in July. Soliman holds undergraduate and master’s degrees in Islamic studies and is pursuing a master’s of divinity and a doctoral degree. It’s not clear why Soliman’s asylum status was revoked, but his lawyers believe it is the result of his 2022 lawsuit against the federal government in which he alleged he was wrongly placed on a terrorist watch list. Soliman has no criminal record except a speeding ticket, though he does have a record of providing care and comfort to sick children as part of his religious work. He remains incarcerated as our government seeks to remove from the country.

There’s Emerson Collindres, a nineteen-year-old young man from Honduras who came to the United States with his family ten years ago. Just days after the high school soccer star graduated, ICE agents seized him and quickly deported him to Honduras, a country he has not lived in since he was eight years old. Collindres’s family had applied for asylum, but the application was denied in 2023. He has no criminal record. Ms. McLaughlin, the spokesperson for Homeland Security, told journalists, “[W]e are delivering on President Trump’s and the American people’s mandate to arrest and deport criminal illegal aliens to make America safe.” As Orwell said, people in power use language — here, “criminal illegal aliens” — to conceal the truth of what they do: in this case, the government deported a good kid and valued member of his community, needlessly casting him out of his home and cruelly separating him from his mother and sister who remain in the United States.

There’s Moises Soleto, a Mexican father and grandfather and the manager of an Oregon vineyard whom ICE agents seized in June. Soleto came to the United States in the 1990s. He has long worked in the local wine industry, was awarded the Vineyard Excellence Award from the Oregon Wine Board in 2020, and started his own business in 2024. It appears he has now been deported.

There’s Robert Diego Alvarez Oliva, who came to the country three years ago, is married to an American citizen, and is the father of a nine-month-old son. Oliva had complied with the requirements of the immigration process, was authorized to work, and had started a business. It seems he missed an appointment with immigration officials because notice of the appointment was sent to an old address. ICE agents seized him on his way to work. He was soon deported to Peru and his family torn asunder by our government.

Other similar stories could and surely will be told since there is little sign the current regime is reconsidering its approach to immigration. For now, this is who and what we are choosing to be. We can choose differently, and perhaps we one day will. It’s up to us because, as Mandami said, we, as a nation, are unfinished.

In the meantime, our darkest contradictions are manifesting in other ways as the current regime seeks to place under its heel a number of civil society organizations, institutions, and entities that have historically acted as a check on the power of government.

The regime is targeting colleges and universities.

The administration has canceled billions of dollars in research funding, touching on virtually every area of academia. It has pressured university presidents to resign. It has sought to restrict universities’ ability to enroll foreign students. It has threatened schools’ accreditation, which would in turn affect their ability to access federal students loans. It has threatened to strip universities and colleges of their non-profit statuses. It has sought to tax schools’ endowments. It has sought to leverage these threats to persuade schools to change whether or how they teach certain subjects. It has launched investigations intended to chill academic freedom and free speech on campus and pressure schools to abandon policies that the current regime dislikes.

The purported reasons for this assault on higher education are twofold: generally speaking, the current regime dislikes what it calls “woke” policies and perspectives. Needless to say, “woke” is a political pejorative, not a meaningful substantive idea. What its invocation really means is that the current regime wants schools to do as it says, when it says, how it says, for the reasons it says. It’s a command not about ideas or principles, but power and obedience, the sort of command we see not in free, open societies, but in authoritarian, closed ones. Second, the regime claims to be targeting anti-Semitism on American campuses. To the degree anti-Semitism exists on college campuses, it should of course be confronted and efforts undertaken to eliminate it, but the available evidence suggests this argument is a mere pretext for pressuring schools into cowering before the current regime. After all, how serious, really, is Donald Trump about tackling anti-Semitism? When white supremacists and anti-Semites marched in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017 chanting, “Jews will not replace us,” Trump said there were “very fine people” among them. Trump previously said he prefers it when Jews count his money, a remark rooted in the anti-Semitic trope that Jews are greedy bankers. He recently held a dinner for the top investors in his crypto scheme, and among them were investors who own tokens named “Fuck the Jews” and several named after variations on Nazi symbols, including Swasticoin. In 2022, Donald Trump dined at Mar-a-Lago with white nationalist Nick Fuentes, who denies the Holocaust, and Kanye West, who has praised Hitler. Trump fans the flames of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories about Jewish billionaire George Soros, who funds progressive causes. These are not the actions of a man who’s serious about rooting out anti-Semitism; his argument that attacks on higher education are about anti-Semitism is simply not credible, and we have no obligation to take it at face value. Instead, we have an obligation to exercise our critical faculties and plainly speak the truth: The campaign against higher education is about bringing schools to heel, and the good news for American democracy is that many colleges and universities are fighting back: The presidents of more than 600 colleges and universities have signed a letter published by the American Association of Colleges and Universities criticizing “the unprecedented government overreach and political interference now endangering American higher education.” Signatories include Ivy League schools, liberal arts college, historically Black colleges, state universities, and community colleges. You may be interested to know that Queens University of Charlotte has not signed the letter.

Cultural institutions, including the Kennedy Center, the Smithsonian, the national parks, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, are being targeted by the current regime. In a move we might expect to see in a tin-pot dictatorship, Trump sacked all Democratic members of the Kennedy Center’s board and replaced them with loyalists who then unanimously elected him chairman of the organization. The board also fired the center’s president and replaced her with a Trump loyalist. As for the Smithsonian, a complex of more than a dozen museums and cultural institutions, Trump has proclaimed that its museums will undergo review to ensure they are aligned with his vision of America and American history. Part of the problem with the Smithsonian, Trump recently said in a social media post, is that it talks too much about “how bad slavery was.” He also recently said that other museums throughout the country may also be targeted for the whitewashing of history. As for the national parks, the current regime has instructed park staff to eliminate anything that “inappropriately disparages” American history while requiring the reinstallation of memorials and statues that honor racist slaveholders and treasonous Confederates, many of which were taken down after Minneapolis cops murdered George Floyd in 2020 and America looked as though it would engage in a reinvigorated racial reckoning. The Trump administration cancelled hundreds of millions of dollars in NEH and NEA grants meant to support artists, researchers, and scholars while Congress, at Trump’s behest, rolled back more than $1 billion in funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which has historically helped to fund National Public Radio station across the country and that announced after its funding was cut that it will close its doors after nearly sixty years of work.

Like other authoritarians, the current regime is attacking journalists and media companies. Donald Trump calls journalists “the enemy of the people.” He accuses reporters of hating the country when they ask tough questions or criticize him, a rhetorical penchant that speaks volumes: in an authoritarian country, the leader is the country and any criticism of him necessarily means the critic hates the country. Real, objective news sources, like National Public Radio and the Voice of America, are being sidelined or attacked while pro-regime propaganda outfits like Fox News, One America News, and Newsmax are elevated. Real journalists are being replaced in the White House Press Room with pro-regime talking heads, podcasters, and conspiracy theorists.

Trump has talked about making it easier to sue news outlets, which he has done over perceived journalistic sleights: He sued CBS for $10 billion, for example, because he didn’t like the way the news program 60 Minutes edited an interview with his 2024 opponent, Vice President Kamala Harris. CBS recently settled the baseless, frivolous lawsuit for $16 million as the company awaited the administration’s approval of a multi-billion-dollar merger with another media company, a merger that was approved shortly after the settlement. Trump sued the Wall Street Journal over its news reporting on his long-time friendship with convicted sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. A reporter for the Wall Street Journal was kicked out of the White House press pool as retaliation for the news story, the same way the Associated Press was barred from the Oval Office because it refused to abide by Trump’s arbitrary command that the Gulf of Mexico now be called the Gulf of America. The regime threatened a criminal investigation of CNN when it aired a report on a new smartphone app — called ICE Block — that allows users to report the whereabouts and activities of ICE agents. The Trump-appointed chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, Brendan Carr, threatened “consequences” for the daytime talk show The View after one of its hosts criticized Trump. Carr also regularly and publicly laments so-called “news distortion” whenever a broadcaster reports news in a way that the regime dislikes, an allegation that can lead to the FCC launching an investigation of the news outlet. And just this weekend, Trump called on broadcasters that publish news reports critical of him to be stripped of their licenses.

The current regime is also targeting disfavored law firms. In an executive order he signed this March, Trump described the law firm Perkins Cole as “dishonest and dangerous” because it worked for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign and, according to Trump, “worked with activist donors including George Soros to judicially overturn popular, necessary, and democratically enacted election laws.” Of course, lawyers are in the business of challenging the legality of laws in the courts. It isn’t dishonest or dangerous for them to do so, but an essential part of a legal system that includes an independent judiciary before whom attorneys appear as advocates for their clients. For this unremarkable behavior, Trump ordered security clearances for the firm’s attorneys suspended. He also ordered any government contractors to disclose if they have business relationships with the firm, an obvious attempt to scare the firm’s clients into firing it with the obvious aim of driving the firm out of business. In another order, Trump stripped the security clearances of attorneys with the firm Covington & Burling because attorneys there worked with Jack Smith, the special counsel who sought and secured indictments of Trump for stealing classified information after his first term ended and for his role in the insurrection of January 6, 2021. And in yet another order, Trump suspended the security clearances of attorneys with the firm Paul Weiss and ordered government contractors to identify any business relationships with the firm, once again with the obvious aim of scaring away the firm’s clients and putting it out of business. Paul Weiss earned the president’s ire because a former lawyer in the office of Robert Mueller, who investigated Trump’s ties to Russia and Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, worked there. Other orders have targeted other firms, and while their details might differ, each is essentially the same: the President is using his vast authority to target and silence his political opponents. While some firms have fought back, others have acquiesced in an attempt to stay in the leader’s good graces, a common habit under authoritarian regimes, together offering nearly $1 billion of free legal work in service to the President’s pet causes. Once again, we choose whether authoritarianism will take root here, and some of us are choosing to make it so.

And then there is the regime’s tendency toward strongman tactics and its general hostility toward democracy. Over the objection of Governor Gavin Newsom and in an act of authoritarian theater, Trump deployed 2,000 National Guard troops to Los Angeles in response to immigration protests. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem, at a Los Angeles press conference at which security personnel tackled and handcuffed Democratic Senator Alex Padilla when he sought to ask the secretary a question, proclaimed she and the current regime were coming to “liberate the city from the socialists and the burdensome leadership this governor and that this mayor have placed on this country and what they have have tried to insert into the city.” Let’s unpack this: Noem is saying that United States military personnel were deployed into an American city to liberate it from the policies of the duly and democratically elected mayor and governor. It is difficult to imagine a perspective more hostile to democracy.

Trump recently activated the National Guard in Washington, D.C. to fight what he describes as a crime wave despite historically low rates of crime. In an attempt to curry favor with the administration, GOP governors from Tennessee, West Virginia, South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Ohio are also sending troops to D.C. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth announced just last week that these military occupiers will now be armed: American soldiers will be training weapons of war on American citizens in an American city. It is an axiom of American democracy that the military occupation of an American city for the purpose of targeting American citizens is abhorrent. That the military is being used in this manner is among the surest signs that the axioms of American democracy may no longer matter because American democracy may be slipping away. Trump has said he plans to consider doing likewise in other cities, specifically calling out New York and Chicago last week. This weekend, after Maryland Governor Wes Moore criticized Trump, the president threatened to send troops into Baltimore. And just today, in the Oval Office, while touting his plans to send troops into more American cities, Trump falsely claimed, “A lot of people are saying maybe we’d like a dictator.” He said this on the same day that Stephen Miller, one of his top advisers, described the Democratic Party as a “domestic, extremist organization,” an observation that suggests the current regime sees Democrats not as fellow Americans, but as enemy insurgents who must be defeated and eliminated by whatever means necessary, up to and including lethal violence.